CENTER STAGE: The Cambodian Aesthetics of a “Spiral Composer”

an Introduction to the Music of Chinary Ung

An on-going column by Edward Green

![]()

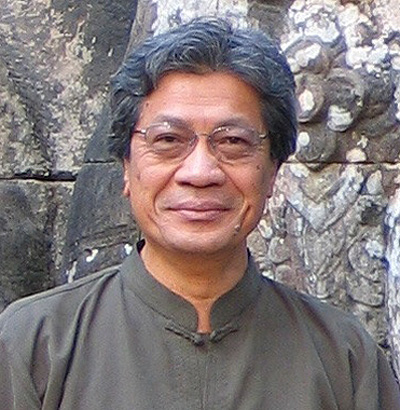

As I mentioned in my inaugural column, the purpose of these essays is to bring attention to composers who have created works of extraordinary merit, yet who have largely been placed on the periphery of the “New Music World.” The first column dealt with Robert Simpson of England; this, with a composer who contrasts with him in almost every regard: Chinary Ung.

Born in Cambodia in 1942, Ung came to the Unites States in 1964 to study clarinet at Manhattan School of Music. Ten years later, he received a doctorate in musical composition from Columbia University, where his principal teacher was Chou Wen-chung. In this initial stage of his career, Ung’s music was largely Western and abstractly modernist in orientation. But then a more unique style arose—a more personal and a more profound style. It emerged out of an intense engagement by Ung with the reality of the Cambodian Holocaust. As Ung has said, his purpose changed; it was now to “employ music as an agent of spiritual healing.”

The Vietnam War had created terrific political instability in Cambodia, which led to the brutal rule from 1975-1979 of the Khmer Rouge. Nearly two million people died—over a fifth of the population—including many of Ung’s own friends and relatives. Stunned by all this, and hoping to find a way to respond with beauty, kindness, and usefulness, Ung studied, as he never had before, the culture of his native land: an artistic and spiritual culture millennia in the making, but nearly destroyed by the actions of Pol Pot and his followers.

In the years between 1974 and 1984, focused on these studies and on humanitarian efforts towards Cambodia, Ung completed only a single piece of music. But a striking change had occurred. In Khse Buon—a 17 minute, one movement work from 1980 for solo viola (the title means “four strings”)—we hear Ung’s new and deeply compassionate voice.

On a technical level, one cannot say if this is avant-garde music, or music which is enduringly traditional. It is at once Cambodian in its primal vocabulary, and yet syncretic, making use not only of the resources of 20th-century modernism but also of the tonal and temporal concepts of Indian, Japanese, and Indonesian music—doing so, moreover, in a manner that is deeply integrated. The charge of trendy eclecticism, so justly made regarding many other contemporary composers, is absurd in relation to Ung. The elements just mentioned are as organically merged in his scores, as French, German, Italian, medieval, baroque, and incipiently rococo elements were in those of Bach.

Moreover, Khse Buon has a design that reconciles two basic notions of time. It plainly evolves forward, and yet just as plainly floats free of the imperative of temporal dynamism. This remarkable feeling for time is equally present in his 1985 Child Song, scored for alto flute, viola, and harp—the work which marked the true end of his “compositional dry spell.” Since then, Ung has been an enormously (and continuously) productive artist. Khse Buon and Child Song, incidentally, are both on a recently released CD from Bridge Records, along with a rare work of Ung’s for solo piano, Seven Mirrors, composed in 1997.

Ung’s music is almost entirely tonal, but it is a tonality with hardly a trace of functional harmony in it. Rather, its strong sense of center (or “centers,” since he often designs his works with a modulatory plan) arises as a direct outcome of the long-limbed, slowly evolving modal melodies he uses—melodies which are invariably highly inflected, and which usually are presented in a heterophonic manner. As far as I can tell, Ung rarely gives a musical phrase without some presence of pitch bending and/or other forms of exquisite, and often dramatic, ornamentation. Just as frequently, there is a series of meaningful timbral transformations, often on a single pitch.

By considering the various technical matters I’ve just described, we get to where Ung, unique, and very specifically Cambodian as a composer, is simultaneously a “universal” artist, working in the mainstream of what is most enduring in human aesthetics. And that mainstream is philosophic. Wrote the great American poet and scholar Eli Siegel in 1962:

Reality is that which is and changes…Things are and change, then, in art. They do so because reality is that which is all the time and becomes different all the time. This essential of reality, as shown by art, is that which is the Aesthetic Center, the essential thing in art. It is that which delights us when, in a detail or in a large whole, we see it. Reality has been seen rightly, and we have come into our perceptive own.

Ung illustrates the meaning of these words in all his finest music, but perhaps nowhere more clearly than in the series of compositions he began in 1987 under the general title “Spiral.” The principle of the spiral is, itself, a reconciliation of opposites: the oneness of linear and circular motion. To trace all the ways this principle is present in Ung’s music is beyond the scope of this short essay, but let me mention one instance: in Spiral VI, a 1992 quartet scored for violin, cello, clarinet, and piano, the tonal center travels, over approximately ten minutes, in a rising series of perfect fifths from C# to its antipode: G. But there is one—and only one—interruption to the pure symmetry of the plan; between the center of F and C, Ung returns to his initial key: C#. We sense the music both “coming ‘round,” and also “moving beyond.” We sense the Aesthetic Center. This work, along with his Grand Alap (1996) for cello and percussion, and his 1991 Grand Spiral (“Desert Flowers Bloom”) for orchestra, can be found on a 2005 CD from New World Records. Seven Mirrors, incidentally, is there, as well.

In a sense, Ung’s technical concern with spiral musical structures can be traced, through his teacher Chou Wen-chung, back to Edgard Varèse (Dr. Chou’s teacher)—who spoke often of the spiral nature of music. Yet the spiritual impulsion behind Ung’s music is clearly Cambodian, deriving from the syncretism of Buddhism and Shamanism found in the village music (and religion) of his youth. Nothing is more characteristic of that spiritual culture than the sense of honoring the “openness” of reality simultaneously with its sense of “steady state.” That is, of something never completed, yet always stable; the world as changing and unchanging.

Perhaps Chinary Ung’s masterpiece is Spiral X, for amplified string quartet. It is given a phenomenal performance by the Del Sol Quartet on their 2008 CD Ring of Fire, subtitled “Music of the Pacific Rim.” (The CD includes works by Zhou Long of China, John Adams of the US, Jack Body of New Zealand, and Hyo-shin Na of Korea—among others.). Given by Ung the subtitle “in memoriam,” his quartet is a harrowing but ultimately consoling work; a quasi-shamanistic exorcism of the evil embodied in the Cambodian Holocaust. In it, Ung seems to hearken back to the traditional Cambodian arakk ceremony, in which a medium enters a trance state (with musical accompaniment) for the purpose of identifying the root cause of an illness. In these ceremonies, music is literally seen as a “healing art,” and that, apparently, is how Ung thinks about music, as well. All of his remarkable, sophisticated musical gifts are applied for this end; and his recently premiered Spiral XII, scored for singers, instrumentalists, and dancers, shares this purpose. It is subtitled “Space between Heaven and Earth,” and it, too, is a portrait of those terrifying events from the mid 1970s, whose scars the Cambodian people still deeply feel. It, too, aims at emotional transfiguration.

Having mentioned singers, it is crucial, in understanding Ung’s musical personality, to realize that perhaps more than any other composer, past or present, he insists that his instrumentalists—while playing—also sing, whistle, chant, and otherwise use themselves vocally. This, for example, is one of the striking features in Spiral X. There are words in several languages, and also ecstatic vocables. While only four musicians are involved, for many passages, there are eight entirely separate musical lines. Chinary Ung might as well have called the piece an Octet for Four! And this surprising junction of the instrumental and the vocal can be found in literally dozens of his works. Here again, he is quintessentially Cambodian—for every serious scholarly study of that nation’s music points to the prominence, in its tradition, of vocality. (See, for example, the various essays of Sam-Ang Sam.)

Chinary Ung is blazing a new path. What makes it worth hearing is that it is a beautiful, courageous, honest path—surprising not only for the vivid, vibrant, haunting sounds we encounter on the way, but also for the conscious kindness which made for them.

Dr. Edward Green, who teaches at Manhattan School of Music, is an active composer whose concerti for trumpet, piano, and alto saxophone were all recently released on CD—each on a different label. Among his scholarly publications are studies of Partch and Ellington, and a book co-edited with Lei Liang on recent Chinese music which will be coming out in May, published—in Chinese—by Shanghai Conservatory Press.