In This Issue (Vol.16#2)

![]() Well, we sure are hearing quite a lot these days about those rotten apples turning our economy into a nightmare. One supposes that this is the news that sells; it certainly doesn’t help the economy to know all of that. We don’t hear nearly as much about real heroes, those among us whom we can claim as genuine national treasures regardless of the state of the national treasury.

Well, we sure are hearing quite a lot these days about those rotten apples turning our economy into a nightmare. One supposes that this is the news that sells; it certainly doesn’t help the economy to know all of that. We don’t hear nearly as much about real heroes, those among us whom we can claim as genuine national treasures regardless of the state of the national treasury.

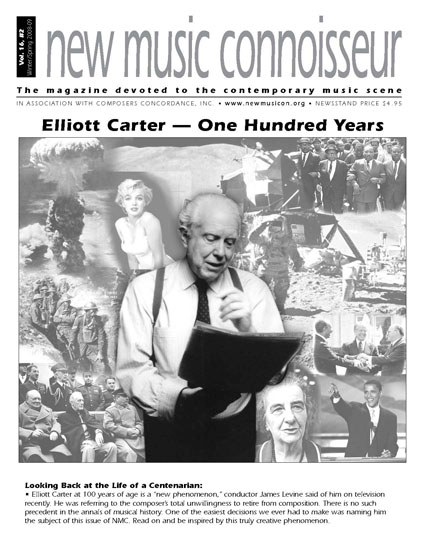

Certainly one of them is the man who just reached his hundredth birthday anniversary, Elliott Carter. But how many Americans at the moment have even heard of Elliott Carter? Isn’t that one of our problems? There are few if any celebrations by the mass media on his behalf. He’s not being interviewed by Barbara Walters or Katie Couric. Nobody is selling Elliott Carter T-shirts. They’re not even writing about him in People magazine, and that makes him a virtual non-person, one supposes. This rampant dumbing down isn’t even appealing to the positive instincts in us. The media are far more interested in playing “gotcha” than saying “you betcha.”

So it was an unexpected joy to turn on PBS’s Charlie Rose the other evening and find this thoroughly alive “treasure” having fun in a conversation with the moderator, conductor James Levine and pianist-conductor (and recent author) Daniel Barenboim. Carter continues to amaze with his alertness, articulation about music and marvelous sense of humor. We know he wears high-powered hearing aids, which he swears by, and which he surely had on for this occasion. When others of his age are either nodding off or trying hard to fathom the conversation, his keen involvement was something to behold. Some time after the pianist had made the point about Carter’s music having an “innate complexity,” the composer threw him a neat left-handed compliment. “I was impressed by the fact that you knew when you were playing wrong notes in my piece,” he said, referring to Interventions, written just for the birthday party. After some laughter it tended to quiet Mr. B down and allow Levine to get in a few licks. But in all honesty the conversation was always uplifting, a surprising fact considering that very little hot air was issued. Okay, there were a few verbal balloons to pin-prick.

One of those balloons was not so easy to burst. Explaining why Carter is not an ordinary composer, Barenboim said, “Too many composers calculate how to write a piece of music; they see thematic and other connections without hearing what they are writing.” Sound familiar? No? Well, maybe he is saying it a lot better than we have been over the years. After all, the pianist speaks with some gravitas. Carter is not hesitant in talking about his music as language that has been absorbed by experience and that an American is ikely to express differently than, say, a Frenchman or German. It’s all about the relationship between music and speech, and that’s aside from the obvious fact that when one writes a song the words must be tailored to music and vice-versa. Carter has tried to be a communicator, whether in his solo works, like Shard (for solo guitar), which we once described as a short but perilous walk through broken glass, or the just completed Sinfonia which is complex and lengthy.

Whether Rose knows that much about music or not, he did come up with good questions. After much discussion about the interpretation of Carter’s music, he asked, “Have you ever listened and said, ‘they didn’t play it the way I intended it but I liked the way they played it’”?” Carter said yes to that, precipitating further discussion about the response to his musical ideas. He strongly feels performers should try to understand the composer’s intentions; otherwise, “it’s just a lot of machinery.” He demonstrated his hatred of sight-reading sans discussion, explaining that such an ensemble in Europe played a work of his fine the first time but he found that each ensuing performance got worse and worse.

Obviously Mr. Levine agrees. In his method of rehearsing there is a first reading by the orchestra and, at the break, he asks the composer for some fine-tuning. Interestingly, Levine insisted that, in the process, the things he found he did not like, the composer also did not like, showing how close the conductor is to a full understanding of Carter’s music. No surprise there, as Levine has now commissioned and played a half-dozen works by the composer since assuming the leadership of the BSO.

Does Elliott Carter have to struggle to write music? To hear him tell it, it’s like a walk in the park. He conceded to only one fact about aging. “I’ve just written what I wanted to write. Of course, it takes more time [now] to write a lot of notes on a page.” A modest admission, to be sure. Just his determination at age 100 to keep on writing prompted Mr. Levine to call that a “new phenomenon.”

Rose’s final question, “How would you sum up your first hundred years,” brought the response that perfectly summed up Mr. Carter’s outlook on life and the world. “I am not aware of being one hundred years old.” To that, this 77-year old preponderately secular listener could not restrain himself from muttering, “God bless you, Elliott!”