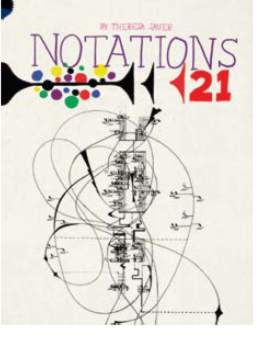

Theresa Sauer: Notations 21

Published by Mark Batty Publisher, New York 2008

by Frank Retzel

![]() “We live in an incredible time in music history – here is only a small sampling of the evidence.” With these words from the Preface, Theresa Sauer launches her 40-year revisiting of John Cage’s unique book Notations. As Cage sampled the notational evidence at mid-20th Century, Notations 21 is timely with its view of score practice early in the 21st century. Like Cage’s book, numerous composers are represented (here over 100), placed not according to the type of music but alphabetically.

“We live in an incredible time in music history – here is only a small sampling of the evidence.” With these words from the Preface, Theresa Sauer launches her 40-year revisiting of John Cage’s unique book Notations. As Cage sampled the notational evidence at mid-20th Century, Notations 21 is timely with its view of score practice early in the 21st century. Like Cage’s book, numerous composers are represented (here over 100), placed not according to the type of music but alphabetically.

Composers were asked to contribute a small section of one or more compositions and were asked to write a statement or description about their work. Several of those commissioned treated the book as a forum and submitted essays on topics such as notation, contemporary music, graphic notation and the creative process. I totally agree with Sauer – “all are completely fascinating and unique.” At 320 pages, 8 1/2 x 11 inches format and color used throughout, this is a gorgeous book, as visually striking as it is provocative.

Comparison with Cage’s book is unavoidable, and here we see some glaring differences in subject approach. The 1968 Notations uses a cross sampling of graphic and indeterminate scores and those in conventional (or nearly so) notation. One noticeable difference is that virtually all examples are in the composer’s hand. Several contributions are of composer sketches. There also seems to be a democracy of musical styles with conservative and radical artists existing in a peaceful kingdom. The accompanying text was typical Cage: one to sixty-four words (often cryptic) chosen with I-Ching chance operations and applied to the two hundred and sixty-nine composers. Notations is for a specialized reader, one who understands mid-20th Century notation and the many styles in existence. There is a wealth of personalities revealed in the examples chosen and in the composers’ manuscript. Creative processes and work methods are often reflected in the writer’s pen. Here is Aaron Copland’s thought on the matter: “Examining a music manuscript, inevitably I sense the man behind the notes. The fascination of a composer’s notation is the fascination of human personality.”

Beyond the examples of contemporary manuscript, Cage provided a few examples of music where score beauty is on an equal par with the distinctive quality of the music (eg. Roman Haubenstock-Ramati’s Mobile for Shakespeare). Graphic or indeterminate notation often could approach the level of conceptual art where the visual beauty of the score was equal to the sound upon realization. It is with this type of score that Notations 21 really hits its mark. From one page to the next we are presented with a bevy of pages suitable for framed display. Is the visual beauty, though, the only criterion for inclusion?

Theresa Sauer takes a cue from composer Earle Brown. After quoting the innovative composer on ‘open’ or ‘available’ form she writes “In other words, the identity of notation comes from its purpose for the creation of music, a phenomenon that can allow for spectacular variations in musical scores (Foreword p. 10).” She writes that she has “examined this phenomenon and the impact it has had on performance as well as our collective consciousness as consumers of art and music.” The result is Notations 21.

From one piece (and composer) to another we see the “spectacular variation” spoken of in the Foreword. There is the occasional work in traditional pitch/rhythmic notation. These all are of an evolved modernist aesthetic. Then, there are a great variety of graphic scores and scores that equally impact the visual and aural. A wonderful feature of Notations 21 is the composer’s note following many of the score pages. These help to explain the notational symbols and the visual component and/or provide a program note of meaning. There are some wonderful essays that examine the concept of notation in today’s world or more directly in the particular writer’s world. Here’s a small sample. After presenting composer Robert Fleisher’s Mandala 3: Trigon for soprano saxophone in score, a concise set of notes explains how to read the music. Following this, Fleisher’s essay ‘Being of Sound (and Visual) Mind’ explores the topic of notation via Cage’s book, Schoenberg’s concept, the visual/aural sense of Klee and Kandinsky, through Crumb and Haubenstock-Ramati. Four very unique graphic works are presented by composer William Hellermann. Following this is an extended letter written to composer Philip Corner to discuss “Score Art.”

Theresa Sauer, the composer who put the whole volume together, is represented by her work Parthenogenesis, written for da’uli da’uli (a kind of xylophone) and an unspecified number of female voices. In the note, she states that “the mother Komodo dragon and her genetic code are the source of all the lines and other designs within the score (p. 207).” A further program note discusses the meaning of ‘parthenogenesis.’ I’d love to see the rest of the score. That holds true for so many examples in Notations 21. Considering that a certain number of these are a type of intermedia (e.g., the visual is a notational trigger for the audio), I am curious how the style and design of notation might dictate the style of the individual composer, and might dictate the style of the realized composition. I have thought for a while about this very thing in my own music and am intrigued to see a volume exploring the same concepts.

My only criticism is that music of a more conservative nature (in sonic design and notational directive) is not included. So many countries and cultures, so many traditions of music are represented that anything possible would seem to be covered. Yet, going from the earlier compendium of Cage’s book with its myriad styles to the 21st Century graphic art of this new volume, one could easily be misled into thinking it reflects the mainstream. What about John Adams, Philip Glass, Arvo Part, film music? Theresa Sauer, in her Foreword, mentions the close deadline facing her after in order to meet the 40th anniversary of Notations . She seems to hope that further editions will come out which can include examples not in this volume. That would be welcome: it truly would allow for the continued Forum on new music, notation, art and music, creative process, etc. already launched.

What we have in Notations 21 is a beautifully rendered volume on notation. Beyond the composers, students and scholars of 20th/21st Century music, one can easily imagine this book in the hands of artists and art historians, and anyone who appreciates a book with stunning visuals. Bravo! II